Cubs’ Chemistry Appears to Have Changed for Worse Over Past Two Seasons

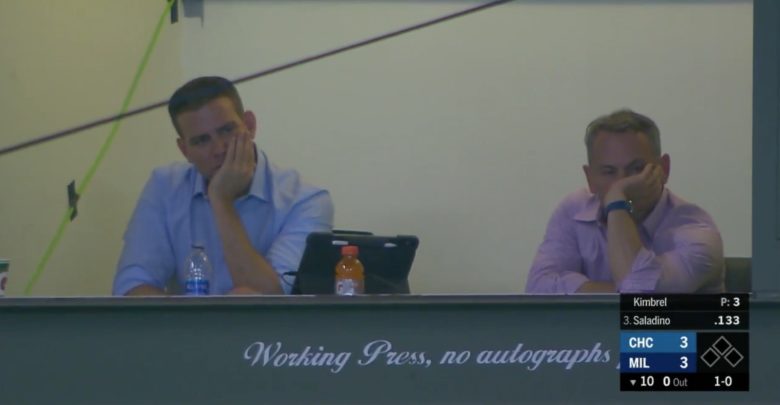

It was once impossible to imagine the Cubs without their enviable and intentional sense of community and chemistry. But we don’t have to imagine any longer, because it has become our reality. At some point over the last 18 months, the Cubs’ organizational chemistry changed.

During spring training in 2018, Joe Maddon lauded “the way that the guys interacted,” talking about how they hung out away from the diamond bonding over more than just baseball. With a few games remaining in the 2019 season, though, it sounds as though the manager no longer believes his guys are interacting on a substantive basis.

“If you want to look into [the road losses] any more deeply, it may have to do with behavior before the game, what you do,” Maddon told the press before Tuesday’s game in Pittsburgh. “I’m not accusing them of going out at night, because I wish they would. That’s the one part of this game we’re missing is that guys don’t go out and have a beer and talk about stuff.”

In just one season, Maddon went from praising team communion to questioning it in the midst of a disastrous collapse. Is poor team chemistry to blame for the Cubs’ struggles, as Maddon speculated?

Defining chemistry or culture is difficult and will vary from person to person. I view it as the ability for players, coaches, and team executives to freely exchange ideas in a non-judgmental environment. Successfully cultivating that kind of situation can lead to the kind of rapid on-field adjustments that ultimately create wins.

Team chemistry is a proxy for collaboration among individuals at all levels of an organization. For example, Anthony Rizzo trusted previous assistant hitting coach Eric Hinske so much that he bought into Hinske’s advice to crowd the plate. That major change turned Rizzo into one of the best hitters of this decade and greatly improved his production against left-handed pitching.

The team collectively embraced the concept of mindfulness in 2016 (highlighted by meditating bear shirts many players wore), which they believe played a major role in their success. That World Series championship team — built by innovative draft strategies and paradigm-shifting international free agent-signing philosophies — overcame hardships by making adjustments and overcoming barriers with ease.

Maybe the reason so many Cubs players have failed to adapt this season is because of suboptimal team chemistry, which has boiled to the surface over the last year or two due to annual coaching changes and an unfamiliar front office tone.

After the Cubs were three wins away from returning to a second World Series in 2017, Maddon and the front office believed firing John Mallee in favor of Chili Davis was the right move. Maddon believed his hitters, who’d earned bachelors degrees in launch angle under Mallee, would be going to “graduate school” with Davis as the new department head.

That hire backfired in a big way, as Davis was fired by the Cubs after just one season due to what Theo Epstein described as a “broken offense.” Not even 48 hours after the Cubs were eliminated from postseason contention in 2018, Epstein blasted his team and questioned their urgency and ability to show up for 162 games. That tone was a sharp contrast to the optimism and encouragement Cubs fans and players had been accustomed to hearing.

Epstein’s poignant words followed a 2018 season in which Willson Contreras, Ian Happ, Addison Russell, Albert Almora Jr., and Kyle Schwarber — all key members of a core the Cubs had developed — underperformed. Much to Happ’s dismay, his particular failures led to a demotion to three days before the start of the 2019 season. The versatile switch-hitter admitted he was angry about the decision, perhaps because he felt blindsided by it. Was that a sign of Happ’s hubris, or a lack of communication on the part of the front office?

Maybe it’s just a matter of too many cooks spoiling the soup. It was as if Maddon’s staff has had more revolving doors than a skyscraper over the last few seasons.

Anthony Iapoce was hired to fill the void at hitting coach for the 2019 season, making him the third man to hold that role in as many years. Iapoce represented a return back to the basics because he was part of the Cubs system through the 2015 season. Contreras’s numbers suddenly returned (.371 wOBA) to normal and Schwarber bounced back from another failed experiment at leadoff — Schwarber even out-hit Cody Bellinger in the second half (400 wOBA vs. .358 wOBA).

But most other players and nearly every single bench bat failed to make the necessary adjustments. Three years and three coaching staffs and, still, several once-promising young Cubs players didn’t improve. All of a sudden, we’re discussing top-tier prospects as disappointments, non-tender candidates, and trade fodder.

Adding Addison Russell, who was suspended under MLB’s domestic violence policy, back into the clubhouse didn’t help matters.

Disappointing development was amplified by the attrition of Dexter Fowler, David Ross, and — dare I say it — John Lackey. All of these Cubs legends’ contributions extended beyond individual performances.

Ross worked with one of the most successful pitching staffs and bullpen in 2016 while keeping the rest of the clubhouse accountable. Fowler was one of the most charismatic, outgoing players in Cubs history who would be frequently seen socializing outside the ballpark with his teammates, something Maddon said he didn’t see from his players often in 2019. And you better believe Lackey was keeping people in line.

Ben Zobrist taking a leave — justified as it was — have a negative impact as well. He is one of the savviest hitters in MLB and was expected to set a tone, but his prolonged absence meant looking elsewhere for that strong example.

“[Zobrist] provides leadership is what he does,” Maddon said. “The quality of play has been outstanding. Yes, the batting average and production has been up and down, but he leads.”

We have seen the Cubs struggle to adapt for three seasons now, though it’s not as if they haven’t tried. They’ve fallen short and it’s a running tally at this point, but we’ll avoid rehashing all of that again.

These examples represent deficiencies in team/organizational chemistry that amplified additional problems (e.g., a suboptimal pitching development infrastructure) to the point that we might be closing the book of this era of Chicago Cubs baseball. It’s jolting. Not even in my nightmares did I think these failures would pile up so quickly.